Celebrating Chip Clark: Digitizing Natural History’s Famed Photographer

Today would have been Chip Clark’s 71st birthday. Born on August 20, 1947, his name will bring a smile to, or ring a bell with, anyone in the world of museum photography. For 37 years, Clark served as a photographer at The Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History (NMNH). No matter which world you orbit, the chances are more than good that you’ve seen at least one photo from his vast body of work.

Recently, several employees of The Crowley Company, working for the Crowley Imaging division, were privy to a large portion of Clark’s life’s work as they meticulously digitized more than 104,000 of his slides, negatives and transparencies preserved by the National Museum of Natural History. The collection documents both Clark’s professional work and personal life, which were closely intermingled.

Chip Clark’s Natural History

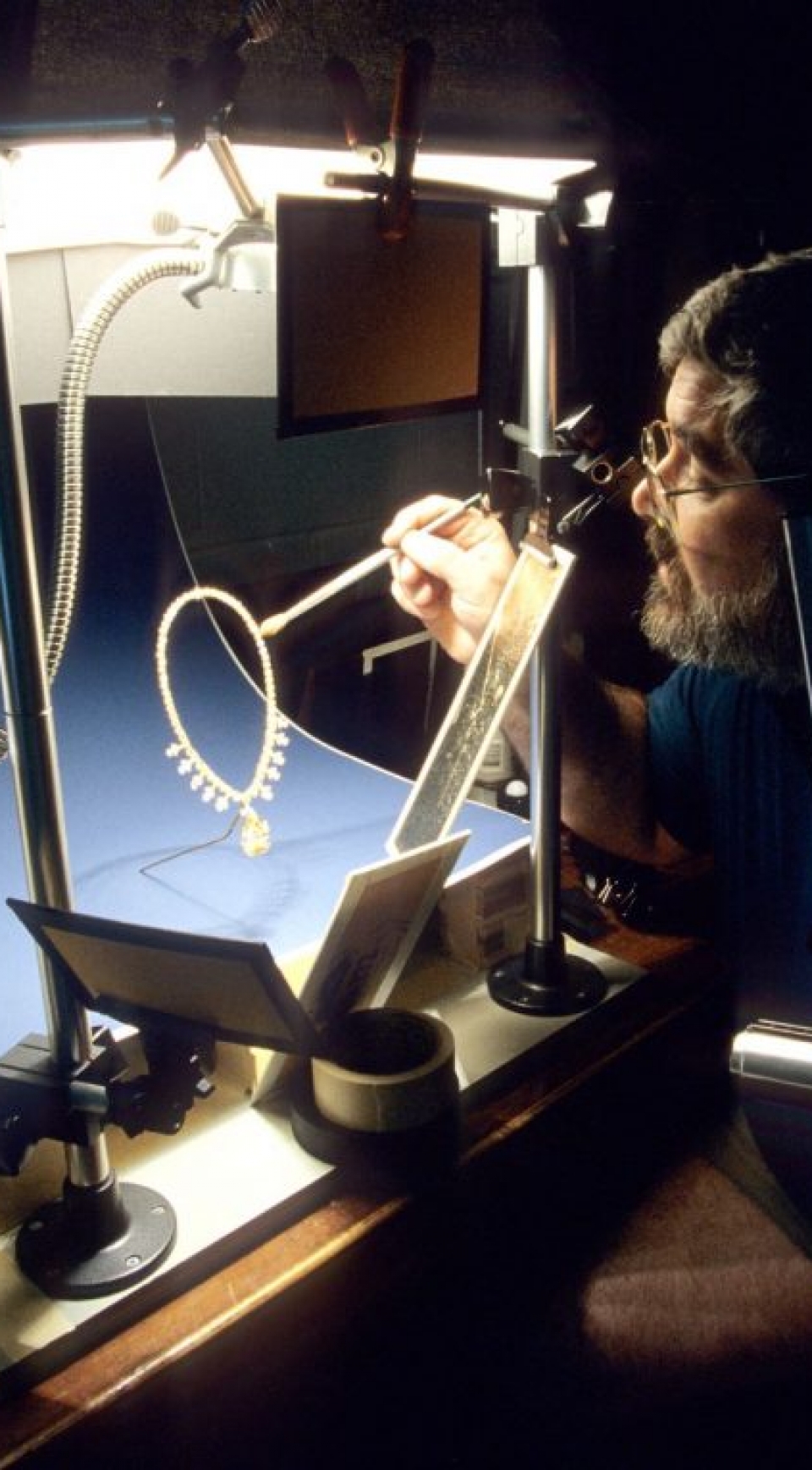

“Chip,” born Roy E. Clark, Jr., came to the NMNH in 1973 with a background in biology and a passion for photography. Working his way to senior scientific and studio photographer, his mission was to document specimens, exhibits, museum community members and to accompany scientists on research trips around the world where his task was to visually document scientific activities and findings. As he lightly says in this live interview filmed to celebrate the Natural History Museum’s 100th anniversary (paraphrased), “By the time I came around, all the nice places had already been studied.” No matter, Clark thrived on the adventure, bringing the rest of the world along with him through his photography.

Throughout his years at the National Museum of Natural History, Clark became an expert at macro photography (capturing close-up details), infra-red and ultra-violet imaging and high-speed and time-lapse cinematography. A brief profile of Chip Clark in a Museum blog post shows some excellent examples of his work.

Interestingly, Clark shot film for all but five of his years, only picking up a digital camera in 2005. In the interview mentioned above, he admits that he was “dragged kicking and screaming” into the digital age. Once there, however, he embraced the technology and quickly realized that all of film’s “quirkiness” that had defined and dictated his career to date – the differing exposure times, lighting, temperature (environmental and film), color challenges, etc. – were now off the table. He was up and running without a look back until his unexpected and far too early passing on June 13, 2010.

Clark’s obituary is understated and as humble as he was purported to be in life. It only briefly mentions his other passion, that of exploring – and, of course, documenting – caves in the United States. His renown is left for those who knew him, enjoyed him and loved him and for those who will continue to discover his photographic genius in the years to come as his work continues to be utilized and profiled.

Outsourcing to Beat the Clock

According to Kristen Quarles, digital collections specialist at the museum, the National Museum of Natural History may sometimes use an outside contractor through a bid process to perform a function that is either not a specialty of the museum staff or which will enhance the efforts and mission of the institution.

In the case of the Clark collection, it was important to have the collection digitized quickly because the window to gather archival information from many of those featured in the photographs is shrinking. Explains Quarles, “In 2013, we started digitizing the collection in-house with a volunteer. As the project progressed, we calculated that it would take at least five years to complete. This didn’t include the gathering of the different levels of metadata which are so critical to an archive. It was imperative to accelerate the digitization process so that we could interview those individuals who are still a part of the NMNH community and have knowledge of Chip’s body of work.”

Additionally, Quarles noted that due to Clark’s renown in the field, his images continue to be requested on a daily basis. The ease of pulling a digital file versus tracking down the location of a slide binder will be an immense time-saver, allowing the NMNH Office of Photography and Media department staff to both respond to requests more quickly and to utilize the saved time on other important tasks.

Quarles concludes with, “There’s also a desire to know what’s in the collection and to make it more widely available. This project is one effort toward fulfilling the Smithsonian goal of broadening public access to our collections and assets.”

The time-sensitive project also had to comply with NMNH Photo and Media’s archival standards, which are comparable to FADGI four-star specifications. Following a competitive request for proposal process, The Crowley Company was selected to undertake the Chip Clark Mass Digitization Project in March 2017.

Digitizing the Analog

As Quarles describes the physical logistics of the collection, the vast scope of Clark’s work, which covers nearly 38 years of history and practically every department at the National Museum of Natural History, becomes quickly evident.

“Chip left behind an enormous collection of film media, processed out to slides and varying size negatives and transparencies. Because he shot his film sequentially, the collection is a mixture of his work for the Museum and his private life, a reminder that film as a medium is unlike today’s digital photography, where you can immediately download files onto a computer and move on.”

Throughout the process of the mass digitization project performed by The Crowley Company, no data or original files left the National Museum of Natural History premises. Crowley imaging specialist Yidnekachew Lachor worked on-site at the Museum of Natural History, switching between a Digital Transitions (DT) IQ3 100MP Digital Back camera system to capture the approximately 1700 120mm, 4×5” and 8×10” transparencies in the collection and a Canon EOS 5DS R for the remaining 102,000+ slides and 35mm negatives. Says Brady Wilks, Crowley graphic arts project manager, “The use of the Canon system, mounted on a custom stand Crowley has designed specifically for slide and negative capture, added speed to the process. This efficiency is critical when manually digitizing a collection of this size.”

The images were digitized at 4000 and 2000 dpi, depending on stated requirements, and the entire process was successful in capturing to, and even exceeding, the FADGI four-star requirement.

For many digitization projects, the Crowley Imaging team will crop, color-correct and output files to TIFF images. For the Clark project, it was required that each image be delivered as a .DNG (Digital Negative) raw file. This created an extra layer of work for the NMNH photography staff. Wilks explains, “Any edits or settings made during capture and processing are lost in the conversion to a .DNG file. Because we shot the slides and negatives from the emulsion side for best image quality, it meant that the images were captured backwards. Saving to .DNG meant that we couldn’t flip the image to its right side as we usually would because that edit would have been lost. Instead, we created a set of instructions for the NMNH staff on how to flip, rotate and adjust as needed.” The .DNG requirement meant that there was little image processing to do on the Crowley side, other than to convert the native Canon .CRT files into .DNG files. This was done remotely via a network attached storage (NAS) unit.

Once the images were digitized, Crowley Imaging staffers Nicole White and Colin Hedden hand-keyed the first level of metadata, the information contained on the slide mount or negative files.

The remaining post-processing will be performed by the NMNH Office of Photography and Media department, which has three photographers and a digital media specialist on staff, all trained in photo editing for archival standards. The first step, says Quarles, will be sorting the now digital collection into more orderly sub-groups. Then, additional metadata, including information from NMNH staff and family interviews, will be added to the files, after which they will be processed for archiving in the Smithsonian’s Digital Asset Management System.

Organizing the Digital

Although there is still a lot of work left to accomplish before the digitized files can be permanently archived, Quarles is looking forward to the opportunity to review Clark’s photographic collection in its entirety, especially the more candid shots that capture behind-the-scenes moments that very few people have seen.

But even more exciting to Quarles is the chance to share these images and the moments they capture – carefully posed and perfectly candid – with the rest of the world. Now in a digital format, Chip’s collection can be distributed more easily and more widely – allowing the world to see the National Museum of Natural History through the lens of the man who was there to capture nearly 38 years of stunning moments and daily activities.

Happy birthday, Chip Clark!

Post Scripts

- You can learn more about Chip Clark’s work in this Smithsonian Magazine article, “The Story Behind Those Jaw-Dropping Photos of the Collections at the Natural History Museum”

- For a fascinating look at the National Museum of Natural History Collection rooms and additional Clark images, visit “Step inside the Smithsonian’s incredibly organized hidden collection rooms” on the Business Insider

- Clarke is buried in Congressional Cemetery. Read here about Crowley Imaging’s digitization of their historic cemetery records.

HAVE A MASS DIGITIZATION PROJECT ON THE HORIZON?

For more information on the conversion services offered by Crowley Imaging or the scanners that can be purchased for your own digitization efforts, please visit our website or call (240) 215-0224. General inquiries can be emailed to [email protected]. You can also follow The Crowley Company on Facebook, Twitter, Google+, LinkedIn, Pinterest and YouTube.

Hi, I lost track of Chip after college and only recently learned that he passed 11 years ago. At Va Tech, Chip’s nickname was Phantom. I spent many hours underground with him assisting in cave photography; one photo in particular won the NSS photo contest that year. We were both SCUBA divers and in addition to running the VA Tech Scuba club we dove in nearby Mountain Lake and in the summers any place that had water (rivers and quarries). Once when sadly a student drowned in a river Chip and I brought his body to the surface. We had many adventures underground and under water. He was a good friend.

Jerry McCoy

Thank you for sharing, Jerry. We’re sorry for the loss of your friend; Chip certainly left a lasting legacy.